Today, 100 years ago, Beyers Naude was born in South Africa. “Oom (Uncle) Bey” as he was affectionately and respectfully known, died in September 2004. This is the obituary I wrote to honour his passing (first published by Independent Newspapers, on 7 September 2004):

By Colleen Ryan

South Africa has lost one of its finest sons in the passing of Beyers Naude.

We mourn his death but we celebrate his life because he proved that the impossible is possible.

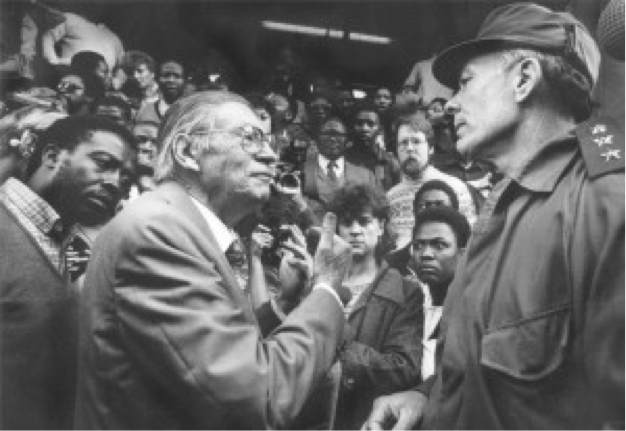

During the long, barren years of apartheid rule, when black and white seemed hopelessly divided, Beyers was a sign of hope. And in the dawn of the new South Africa, he stood alongside Nelson Mandela as a symbol of reconciliation.

The respect Beyers earned in the black community stemmed partly from his background as a white Afrikaans church leader.

Many black people seemed to intuitively understand the price that he

paid among his own people for opposing apartheid.

He will be remembered as a great South African who made an important contribution to justice and reconciliation. While most white South Africans chose to look the other way, Beyers was their voice of conscience, warning of the consequences of an unjust political system.

In the beautiful Highveld autumn of 2001, after Beyers took ill, both former president Nelson Mandela and President Thabo Mbeki called on him at his Northcliff retirement home.

He was deeply touched by their visits. In a letter written by Beyers and Ilse Naude to their friends they said: “It is extremely gratifying to know that one’s life’s work has not been in vain and is still being commended.”

A man of faith, compassion and courage, Beyers believed he was blessed to have witnessed South Africa’s transition to democracy.

His contribution to the liberation struggle went hand in hand with his work in the churches, particularly the Ned Geref (Dutch Reformed) grouping.

He partly attributed his fellow-Afrikaners’ unswerving support for apartheid to the conservative racial policies of the NGK, and he tried for many years to develop an alternative, unified vision for the black and white NG family of churches.

The year 1994 was significant for him not only because South Africa held its first democratic elections but also because he finally made peace with the NGK. Delegates to the NGK synod voted in support of a motion which admitted that the church had disregarded the prophetic witness of, among other people, Beyers Naude. When Beyers and Ilse attended the synod to accept their apology, his fellow ministers gave him a standing ovation.

This moment stood in stark contrast to a bitter Sunday in November 1963 when Beyers delivered his last sermon to his Northcliff congregation before being dismissed for his witness against apartheid.

For the next four decades Beyers devoted himself to bringing justice to South Africa. It was a hard and lonely path, but Beyers was never entirely alone. At his side was a remarkable person – Ilse Naude.

Loyal and indomitable, she did not take an active part in her husband’s political struggle, but they were united by a deep faith in God and their undying love for one another.

A decade ago I wrote a biography on Beyers and spoke to many people whose lives had been interwoven with his.

What they all conveyed, and what I think was most striking about Beyers, was his empathy for people. Oom Bey, as he was respectfully called, genuinely cared about others. Heads of state, diplomats, cleaners, housewives, students or the unemployed – all received a similar reception. He had a way of making people feel that they counted.

Beyers was born on May 10, 1915, into a religious and nationalistic household. His father was a leading NG minister and Afrikaner rights campaigner.

The young NGK minister was regarded as an up-and-coming Afrikaner leader and in the late 1950s Beyers was elected to the leadership of the NGK Southern Transvaal synod.

But he had begun to have doubts about apartheid, and the 1960 Sharpeville massacre, in which police killed 69 black protesters, weighed on his conscience. Shocked by the killings, he played a key role in a World Council of Churches conference held in Johannesburg, which challenged the white Afrikaner churches’ claim that apartheid was Biblically defensible.

In 1963 he formed the Christian Institute to offer churchgoers, especially Afrikaners, an alternative to apartheid theology.

Beyers’s public rejection of the racial policies of his church and National Party elicited a bitter reaction. The NGK ensured that he was defrocked as a minister, and he and Ilse and his four children were ostracised by the close-knit Afrikaner community.

Beyers’s transformation from a revered Afrikaner to pariah was deeply painful, yet the most remarkable years of his life were to follow. Having shown he could change, he continued to adjust his political thinking. During the 1970s he became close to young Black Consciousness figures whose leaders included Steve Biko and Barney Pityana.

Beyers’s close identification with the liberation struggle was not lost on the NP government and in October 1977, the Christian Institute was closed down, and Beyers and other institute leaders were banned.

Ironically, Beyers was most in the public eye during his lean years as a banned person, from 1977 to 1984. Thousands of people made their way to his tiny study in Johannesburg, to discuss strategies for liberation.

While Beyers was heavily involved in politics, his first point of focus remained the churches. Having being defrocked as a minister of the white church, he was welcomed with open arms by the black NGK and served for many years as a minister in Alexandra.

White critics accused him of being a political priest, but Beyers believed his faith dictated his social and political involvement. He asked how one could sit on the sidelines when all around there was poverty, violence and suffering.

After his unbanning in 1984 Beyers served an important two years as caretaker general-secretary of the SA Council of Churches. In the mid- to late-1980s he also played an important role in facilitating talks between the ANC leadership in exile and white South Africans.

In recent years Beyers focused on challenges in the post-apartheid South Africa, identifying reconciliation and corruption as key issues. He helped set up a Transparency International branch, later to become Transparency South Africa, and his involvement in this project showed a characteristic determination to continue to tackle politically sensitive issues.

In 2001, he became only the second person to be awarded the freedom of Johannesburg and DF Malan Drive was renamed in his honour.

Johannesburg executive mayor Amos Masondo encapsulated the sentiment towards Beyers when he commented: “Oom Bey, as we have come to know him over the years, is one of our veteran anti-apartheid stalwarts.This is one person we can say has touched the lives of many, many people.”

I rang Ilse after Oom Bey took ill, and she told me he had asked his friends to pray for him.

“He says he is tired, he wants to go Home.”

God bless you, Oom Bey.

Colleen Ryan is the author of the biography: Beyers Naude – Pilgrimage of Faith and obtained her MA degree in History with Unisa with the dissertation From Acquiescence to Dissent, Beyers Naude, 1915-1977.